Recycling Plastic Does Not Work

I wish it did. Imagine a world where that International Recycling Logo - ♲ - those three twisted arrows - that green Mobius loop - actually spun perfectly. “Reduce, reuse, recycle.” One would be able to consume as much material as they wished knowing that it came from a green source and 100% of it could be later used. There would be no eco-guilt associated with consuming plastic. One could spin that wheel FASTER and MORE without any negative ecological worry knowing that the loop is actually closed.

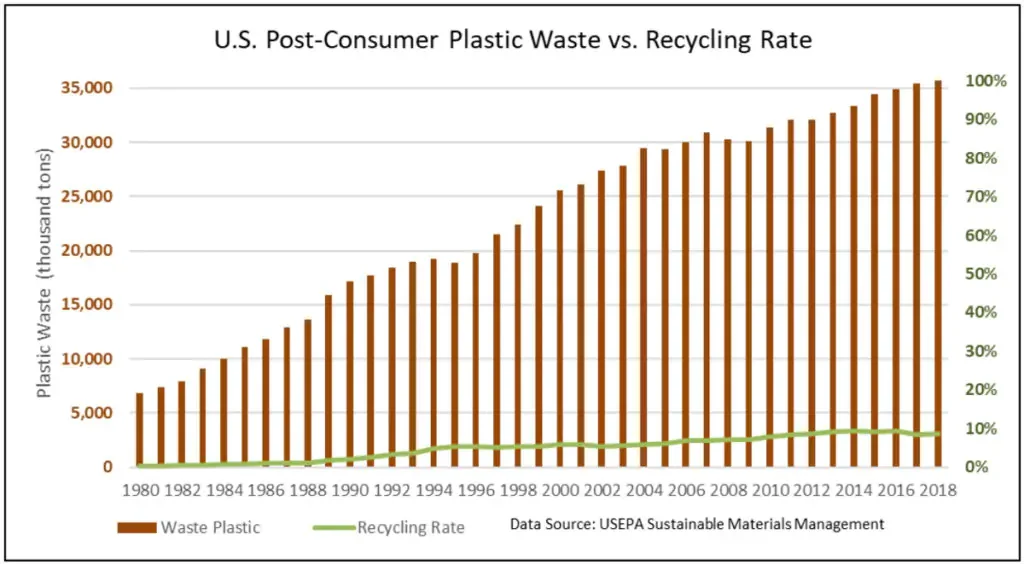

However, that is not the case. The amount of garbage generated per day is growing while recycling rates are falling. Per capita plastic waste generation has increased 263% since 1980 while U.S. plastic recycling rates have declined from about 8.7% to 5%-6% in 2021. The UK produces more waste than it can process; 230m tonnes a year (1.1kg per person per day). The U.S. produces 2kg per person per day, generating more plastic trash than any other nation. Over 40% of plastic produced last year was used once and then discarded. Officials in the Florida city of Deltona said their curbside program was not working and suspended it; hundreds of other towns and cities across the country have similarly canceled recycling programs or limited the types of material they accept.

Recycling is complex. Contamination prevents large batches of material from being recycled. Certain other materials like as plastic straws and bags, eating utensils, yogurt tubs, and takeout containers cannot be processed in certain facilities. They usually are incinerated, deposited in landfills, exported, or washed into the ocean. Plastics with resin codes 3–7 are virtually impossible to recycle.

The simplest and cheapest option is to bury garbage in an environmentally safe landfill, and since there is no shortage in landfill space, there is (arguably) no reason to make recycling a legal or moral imperative. All the garbage produced in the U.S. for the next 1000 years could fit into a landfill 100 yards deep and 35 miles across on each side (0.0124% of American soil). Still, landfills emit carbon dioxide, methane, volatile organic compounds, and other hazardous pollutants. While incineration of recyclables can produce energy, waste-to-energy plants are also associated with toxic emissions. Philadelphia is now burning about half of its 1.5 million residents’ recycling material in an incinerator that converts waste to energy.

The U.S. use to ship its recyclables off to Asian countries, but 30% of recyclables sent to China were contaminated by non-recyclable material, never recycled, and ended up polluting China’s countryside and oceans. 20-70% of plastic intended for recycling shipped overseas is similarly deemed unusable and ultimately discarded. If there is no market for recycled material, the numbers do not work, as cities need to sell materials to recoup costs of collection and transportation, and even that is only ever a portion of the costs.

In 2017, China’s National Sword policy banned the import of most plastics and other materials, prohibiting 24 types of waste from entering the country arguing they were too contaminated. When China stopped taking plastic, it stopped being sold for profit. U.S. processing facilities and municipalities now have to pay more to recycle and discard waste, which they largely cannot afford to do. It costs more to recycle than to dispose of the same material as garbage. There is serious doubt that recycling plastic can ever be made viable on an economic basis. Because the U.S. was dependent on China for recycling for so long, their domestic recycling infrastructure was never developed. Recycling services compete for local funding that is needed for schools, policing, roads, ect. Without dedicated investments, recycling infrastructure will not be sufficient. The market then began flooding any country that would take its trash: Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam, causing ‘waste mismanagement’ - rubbish left or burned in landfills, illegal sites, or facilities with inadequate reporting.

As long as it is cheaper to landfill plastic then to recycle it, recycling will never be economically worthwhile. The U.S. does not have a federal recycling program, and that leads to unorganized competition; recycling decisions are made via 20,000 various communities with many stakeholders and different interests without common ground and end goals. Each UK council collects its plastic recycling differently as well, showing 39 different sets of rules. Communities, recyclers, haulers, manufacturers, and consumers then work against each other. There is no clear, safe, or profitable circular economy for plastic recycling. Recycling resources also cost resources; material must be collected, transported, sorted/separated, and processed. All of those steps produce pollution.

The EPA says that out of the 267.8 million tons of municipal solid waste generated by Americans in 2017, only 94.2 million tons (35%) were recycled or composted. Less than 10% [of plastic] is actually recycled in the UK. 66% of discarded paper and cardboard was recycled, 27% of glass, and 8% of plastics are recycled. Glass and metal can theoretically be recycled indefinitely; paper 5-7 times before it’s too degraded; but plastic only once or twice. Single-stream recycling, where all recyclables are placed into the same bin, results in about 25% of material being too contaminated. Six times more plastic waste is incinerated than recycled. There is too much plastic, and too many different types of plastics, and no viable end markets for the material. Virgin plastic is cheaper than recycled plastic. Not all plastics can be recycled and it cannot be recycled indefinitely unlike glass or aluminum.

All used plastic can be turned into new things, but picking it up, sorting it out by both color and polymer type, reprocessing, and melting it down is laborious and expensive. Accurate sorting is essential, but varies between recyclers, are often not well standardized, and no approach is 100% efficient. Failures in any of these steps can lead to material with inconsistent properties unappealing to industry. Moreover, every time plastic is recycled its quality decreases. Recycling is not a sustainable solution to the skyrocketing amount of plastics being made. Similarly, only 15.2% of textiles were recycled in the U.S. in 2017; food waste is also a significant source of waste. Individuals cannot simply recycle their way out of such crises.

To make matters worse, millions of dollars are spent every year telling people to recycle so industry can continue to sell plastic. If the public thinks recycling is working, they are going to be less concerned about the true dangers plastic has on the environment. Separating my tuna cans makes me feel like I am making a difference when it is a just a smokescream so that the systems in place continue to profit while the issues at large continue to get worse. New plastic is cheap, and is made from oil and gas, owed by giant multinational oil and gas conglomerates.

Exxon, Chevron, Dow, DuPont (with Exxon Mobil and Dow responsible for 55% of the world’s single-use plastic waste) and their combined lobbying worked to make plastic recycling commercials as early as the 70’s. Cut your plastic 6-pack soda rings to save the turtles from choking! Clever marketing and PR; they spent tens of millions of dollars on these ads and ran them for years, even thought it was well known even back in the 70s that recycling plastic was unlikely to happen on a broad scale. The only thing promoting recyclable plastic achieves is the production of more plastic.

Starting in 1989, oil and plastic executives began giant but quiet campaigns to lobby almost 40 states to mandate that the green arrow recycling symbol appear on all plastic products — even if there was no way to economically recycle them. Consumers then looked at the bottom of their milk jugs, soda cans, yogurt tubs, and Chinese food containers, saw the symbol, and threw them all in the same bin and felt good about themselves. That symbol was and is just a ‘green marketing tool’ - nowadays known as a tactic called greenwashing; ‘the process of conveying a false impression or providing misleading information about how a company's products are more environmentally sound”. Small campaigns started to fight such manipulation of the consumer, but no one has the work force, money, or time to compete against big oil. Big oil makes $400+ billion a year making plastic. As demand for oil for cars and trucks declines, the industry is telling shareholders future profits will increase from plastic; plastic production is expected to triple by 2050.

You will hear big oil talk the talking points - that they are invested in recycling more now than ever - but that is not enough to solve this complex problem. It is the same old smokescreen they did in the 70’s; they are not interested in putting real money, time, or effort into solving recycling issues because they really just want to sell virgin material — that's their business – and it has been for decades and will continue to be for decades. McDonald’s, Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Coca-Cola all promise that by 2030 their packaging will consist of 100% of renewable, compostable, or recycled materials, but plastic production will grow by 40% in that time and they will all profit from that growth.

To fix this issue, domestic markets and laws must grow. Companies need to enhance the quality of recycled plastic and incorporate it into the plastic products they produce. Technology for sorting and recovering material needs to improve. Regulations and purchasing commitments must push such change. Governments must limit the disposal of construction and demolition debris. We need more education, incentives, penalties, legislation, and innovation. We need consumer brand companies to adopt strict policies that reduce the production, usage, and disposal of plastics. We need to consume less; I see my coworkers reusing soda bottles (1 in 4 bottles of which are ever fully recycled) until the labels are unreadable to try to be conscientious about this, but that does not scale to global markets. Bringing empty shampoo bottles to refill them within zero-waste shops instead of buying a new one is a nice thought but again does not scale; you cannot put the milkman model on everything we buy. We need large and economic/commercially incentivizing taxes on plastic packaging not containing recycled material. We need more compostable packaging. We need to force industry to invest in recycling infrastructure at home. We need to shift the economy and cost of plastic production to one where recycling products is always more profitable than using virgin materials. We need to develop and use alternative packing materials that have a faster degradation process. Recycling CAN help to reduce carbon emissions.

But this all might still not be enough. Recycling rates in the west are stalling while packaging use is soaring in developing countries where recycling rates are low. The Covid-19 pandemic led to a 30% to 50% increase in the use of disposable goods. Petrochemicals companies rely less on recyclables when the price of oil is low. Recycling aluminum is straightforward, profitable, and more environmentally sound, but plastic recycling remains burdensome. Plastic packaging has actually done an incredible service for the world; it is durable, cheap, waterproof, versatile, and lightweight. Plastics have helped safe food shipments globalize and reduce the amount of glass, metal, and paper used - the less glass, metal, and other materials used, the lower the carbon footprint - but we lack the proper technology and innovations to recover plastics in an economically and energetically feasible way.

To put it bluntly, recycling plastic is costly and infeasible and the economics of the recycling business are broken. There are hundreds of types of plastic that cannot be melted down together, they have to be sorted out, but the costs of separating plastics are high and it cannot be justified economically. These issues have existed for decades, but the general public is unaware of all these problems because they have not been made aware, probably purposefully so. No matter how good the new recycling technologies are, or how many new expensive machines are developed, of the 8.3 billion tonnes of virgin plastic produced worldwide since the 50’s, less than 10% of it has ever been recycled and only ~1% have been recycled more than once. Even high estimations say that we only recycle about 20% of material per year globally.

Recycling plastic does not work and plastic recycling is a lie. Laws are being enacted to "extended producer responsibility" and “promote sustainability” although they are not as strong as they should be and we have a very long way to go before these issues can ever truly be solved. If you think walking an extra block to find a recycling bin for your soda bottle is at all helpful, you are part of the problem.

Sources:

How Big Oil Misled The Public Into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled (2020)

Plastics Recycling ‘Does Not Work,’ Environmentalists Stress as U.S. Recycling Rates Drop to 5% (2022)

Is recycling a waste? Here’s the answer from a plastics expert before you ditch the effort (2021)

'Plastic recycling is a myth': what really happens to your rubbish? (2019)

Thank you all for reading. I post educational material daily. Subscribe to learn more!